Horizon Power’s SAPS system at Cape Le Grand, east of Esperance. (Source: Horizon Power)

On 30th May 2019 the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) released its final report on the “Review of the Regulatory Frameworks for Stand-Alone Power Systems – Priority 1”. The report sets out the recommendations from the Commission for regulatory change which allows Distributed Network Service Providers (DNSPs) to create their own Stand-Alone Power Systems (SAPS) and the implications for this are huge.

The National Electricity Market (NEM) consists of approximately 40,000 kilometres of transmission lines and 850,000 kilometres of distribution lines. The NEM serves approximately 9.7 million customers and there was $17 billion traded on the NEM in financial year 17/18. The NEM represents the largest amount of electrical infrastructure per capita of any electrical grid in the world and is one of the world’s longest continuous end-to-end interconnected power systems running 5,000km from Port Lincoln to Port Douglas.

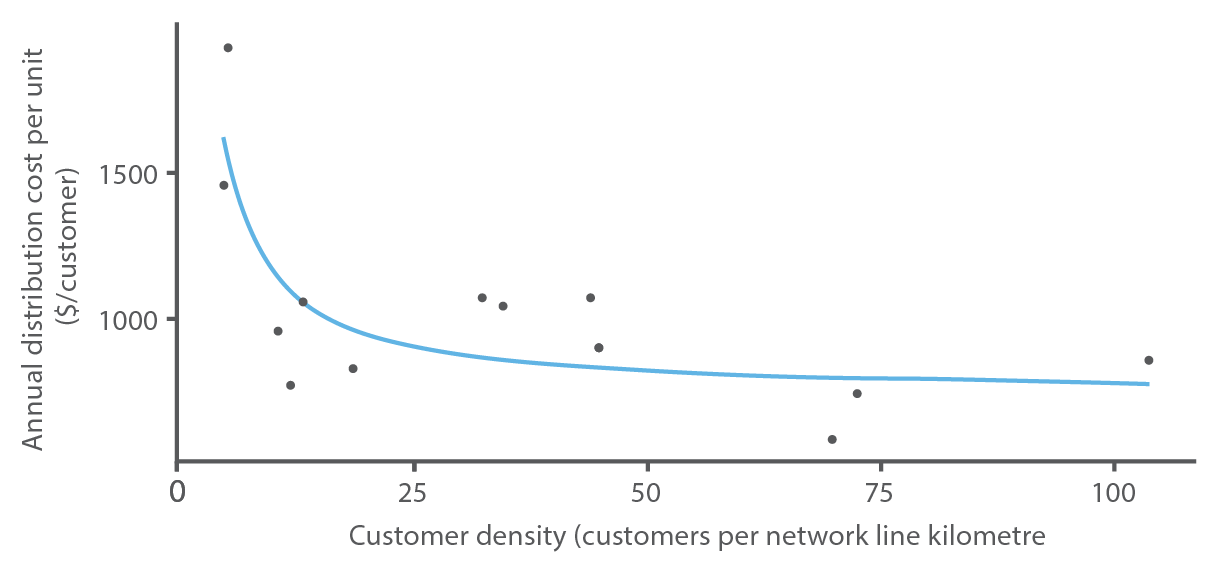

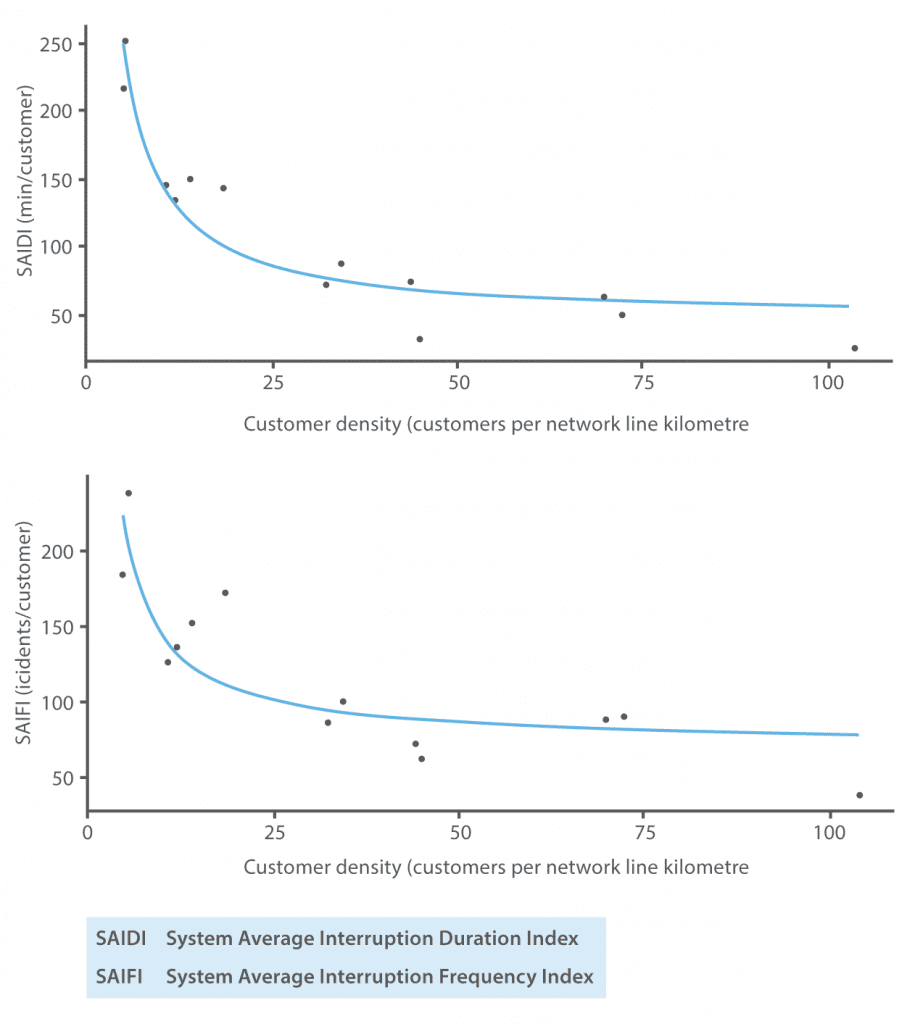

In order to support the NEM, there exists a cross subsidy whereby the cost to service remote electricity customers is socialised and therefore inflates the cost borne by the rest of connected electricity users. Remote customers can cost DNSPs five times as much as an urban customer to serve (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Costs to service remote electricity customers (low customer density) compared to costs to service

urban electricity customers (high customer density).

(Source: DNSP data reported in AER regulatory information notices 2011-2017)

For example, South Western WA (not part of the NEM but overseen by the AEMC) has over 50% of its High Voltage infrastructure dedicated to just 3% of its customers. This situation is not a typical of Australian networks.

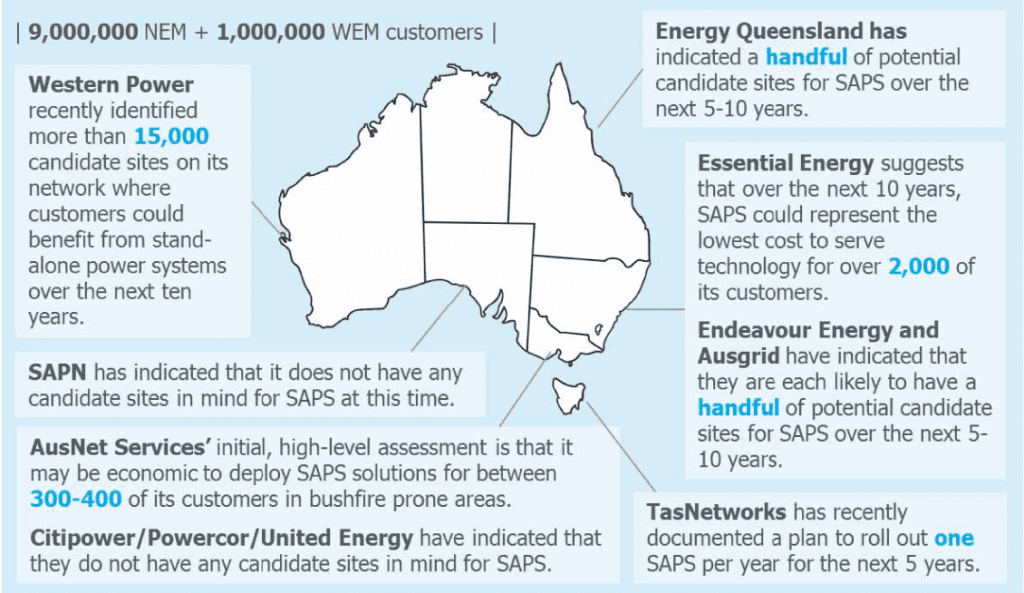

The AEMC report suggests that remote customers would receive higher quality service at a lower cost if the DNSP which currently serves them creates a Stand-Alone Power System to do so. The flow on effects would be lower costs for DNSPs, better service for remote customers and cheaper electricity distribution for all customers. The report attempts to capture the opportunities for SAPS across all Australian networks as per Figure 2.

Figure 2: Opportunities for DNSP-driven SAPS across Australia.

(Source: AEMC)

Although the report was light on opportunity details, suggesting that there were a “handful” of opportunities, networks have been quoted giving big savings estimates:

- Western Power argued it would save $400 million/year when they lobbied for a similar rule change in 2016

- Essential Energy in NSW said it identified savings of more than $220 million due to this potential rule change

- Energy Queensland said that the savings could be in the order of $600 million.

(source: Renew Economy)

Australia wide, the savings could be in the billions of dollars.

The AEMC report lays out the models of supply in order to address how the new system structure would look. It sets out four models of supply:

- Standard NEM Supply: This is the traditional NEM setup with centralised generation, transmission, distribution and

end-users on the demand side. - Embedded Network: This network structure was defined by a number of rule changes made over the past few years

(see Power of Choice Review) and allows private networks and retailers to connect behind a parent meter which ultimately interfaces with the NEM (for example, shopping malls with many tenants where the shopping mall owns its own electricity infrastructure and on-sells energy to its tenants). - Individual Power Systems: These are the traditional SAPS which exist independent from the grid (for example, homes and villages which are off-grid and not governed by NEM rules).

- Microgrid (defined as “isolated from the interconnected grid”): These are Stand Alone Power Systems which contain their own generation, distribution and loads and, as the report suggests, will be governed by the National Electricity Law (NEL), the National Energy Retail Law (NERL), the National Electricity Rules (NER) and the National Energy Retail Rules (NERR) after the rule change is complete.

The report gives recommendations for the creation of microgrids in five areas:

- Planning and Engagement

- DNSPs existing network planning and investment framework is deemed as satisfactory including the Regulatory Investment Test for Distribution (RIT-D).

- DNSPs will be required to report on SAPS opportunities, implementations and projects considered and will need to keep metrics on customer transitions and total SAPS implemented.

- DNSPs will NOT be required to obtain explicit consent from customers in order to transition them to off-grid supply.

- DNSPs must develop a SAPS customer engagement strategy and must issue formal, public notice to affected parties.

- AEMO suggests that customer consent will at least be implicit as they will need to be engaged to ascertain land requirements, load profiles, planned load growth and other technical requirements.

- New Connections and Reconnection

- Newcustomers seeking SAPS will enter a competitive market where DNSPs and third parties will provide SAPS at cost-reflective prices (not required to subsidise service as with existing customers).

- Customers should NOT have a specific, additional right of reconnection to the interconnected grid (AEMC views the SAPS as the DNSP’s grid).

- Service Classification

- SAPS will comprise two components, each providing a separate service:

- A Stand-Alone Distribution System

- A Generating System

- DNSPs will be allowed to operate the distribution system but must procure generation from a third party or subsidiary via the AER’s ring-fencing guideline.

- SAPS will comprise two components, each providing a separate service:

- Consumer Protections and Reliability

- The existing energy-specific consumer protection framework is fit for purpose with regard to SAPS, including the National Electricity Customer Framework and jurisdictional consumer protections.

- AEMC recommends that jurisdictional governments update their legislative frameworks.

- The NERL will apply energy-specific consumer protections to SAPS customers.

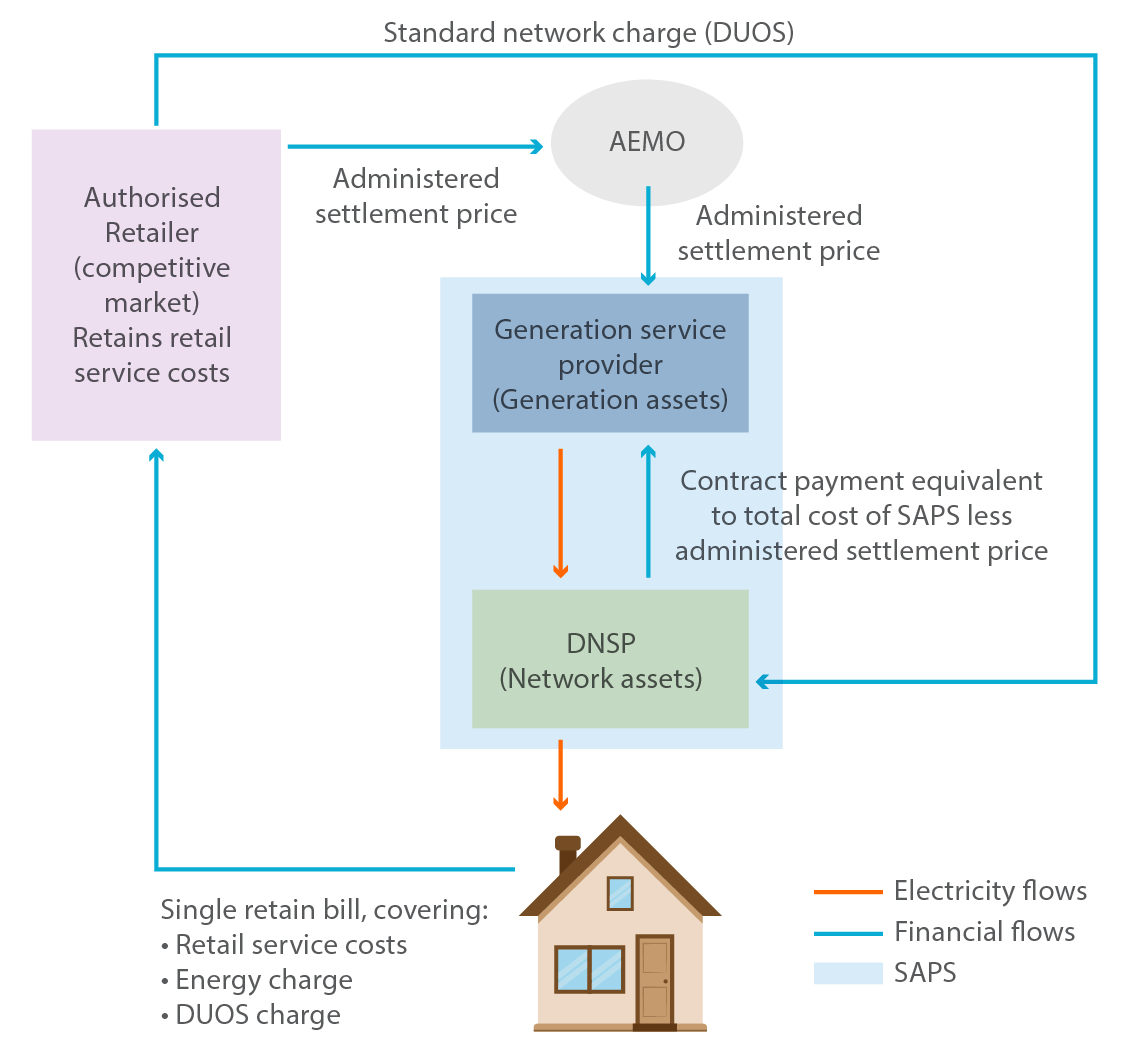

- Service Delivery Model

- AEMC suggests that the existing wholesale energy market arrangement (with regard to retail) is fit for purpose except, instead of 5 minute settlements, retailers will be charged an administered settlement price for energy.

- This way SAPS customers can retain their retailer if they so desire.

- An administered settlement price simplifies the retail process and removes the risk of inappropriate price signaling or hedging to affect SAPS customers (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Recommended service delivery model

(Source: AEMC)

The settlement price mechanism might be the most contentious of the recommendations but it has been put forward as it invokes AEMO, keeping the NEM flavour of the SAPS recommendations. AEMC makes suggestions about the settlement term but says that will ultimately be determined when the rules are drafted. Long settlement periods may leave some opportunity on the table but it creates a simple consumer protection mechanism, which is important in the first instance.

The report suggested that SAPS could reduce the duration and frequency of grid outages (Figure 4: System Average Interruption Duration Index or SAIDI and System Average Interruption Frequency Index or SAIFI respectively).

Figure 4: Grid interruptions compared to customer density.

Figure 4: Grid interruptions compared to customer density.

(Source: AEMC)

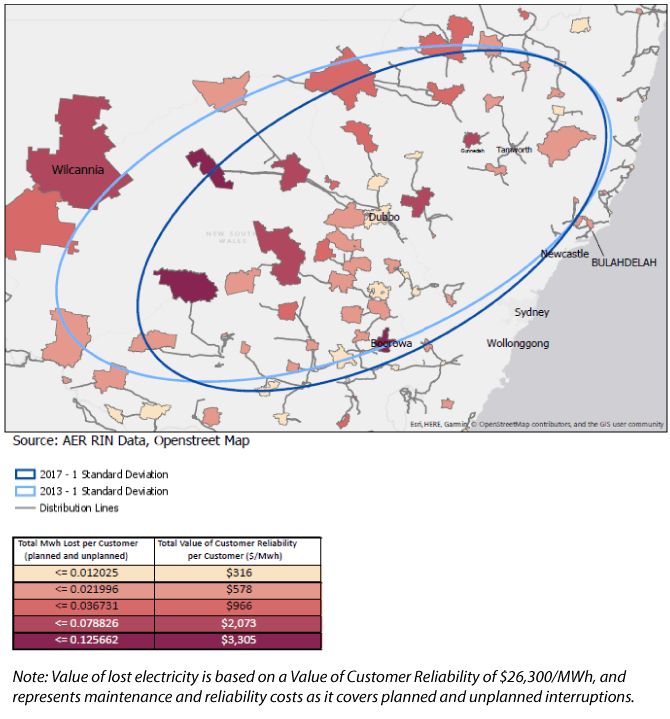

Interestingly, locations which have below average reliability but are more densely populated have a higher economic cost associated with interruptions (Figure 5), therefore the business case for SAPS may not be limited to the very remote. This may make SAPS more interesting than the “handful” of opportunities outlined by the networks initially, especially as solar and batteries continue to move down the cost curve.

Figure 5: Economic cost associated with interruptions.

Figure 5: Economic cost associated with interruptions.

(Source: AEMC)

The report provided an example of a case where a SAPS would make sense over the commonly used Single Wire Earth Return (SWER) lines. It concluded that basically any SWER line over 4km should be turned into a SAPS. Australia operates around 200,000km of SWER lines and many of them are likely to be longer than 4km node to load.

The timeline between this rule change recommendation and the actual rule change is likely to be in the order of 18 months. The implications of the rule change are yet to be seen but it seems like the opportunities that this rule change will present will be big.

GSES provide Stand-Alone Power Systems courses that provide a pathway to accreditation.